De mortuis nil nisi bonum

The Latin phrase De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est, "Of the dead nothing but good is to be said." — abbreviated Nil nisi bonum — is a mortuary aphorism indicating that it is socially inappropriate for the living to speak ill of the dead who cannot defend or justify themselves.

The full Latin sentence is usually abbreviated into the phrase (De) Mortuis nihil nisi bonum, "Of the dead, [say] nothing but good."; whereas free translations from the Latin function as the English aphorisms: "Speak no ill of the dead," "Of the dead, speak no evil," and "Do not speak ill of the dead."

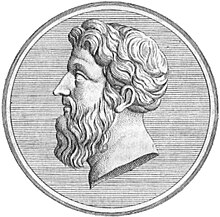

Attributed to Chilon of Sparta, who was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, the aphoristic recommendation about not speaking ill of the dead was first recorded in Classical Greek, as: τὸν τεθνηκóτα μὴ κακολογεῖν ("Of the dead do not speak ill."), in chapter 70 of Book 1 of Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, by Diogenes Laërtius, in the 4th century AD. The Latin version of the Greek mortuary phrase dates from the translation of the book by Diogenes Laërtius, by the humanist monk Ambrogio Traversari in 1443.[1]

Usages

[edit]

Literary

[edit]Novels

[edit]- In The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867), by Anthony Trollope, after the sudden death of the Bishop's wife, the Archdeacon describes De mortuis as a proverb "founded in humbug" that only need be followed in public and is unable to bring himself to adopt "the namby-pamby every-day decency of speaking well of one of whom he had ever thought ill."

- In The Power-House (1916), by John Buchan, after destroying the villain, Andrew Lumley, the hero, Sir Edward Leithen, says "De mortuis & c.", an abbreviated version of the phrase, in reference to the dead Lumley.

- In Busman's Honeymoon (1937), by Dorothy L. Sayers, Lord Peter Wimsey says "De mortuis, and then some," in response to the fact that no one they've met has had anything positive to say about the murder victim.

- In Player Piano (1952), by Kurt Vonnegut, the phrase is used by the narrator after describing individuals "with nothing to lose anyway, men who had fallen into disfavor one way or another, who knew they had received their last invitation" to the Meadows.

- In Deus Irae (1976), by Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny, Father Handy thinks of the phrase in reference to millions of people killed by nerve gas. He then subverts the phrase to "de mortuis nil nisi malum" in blaming them for complacently voting in the politicians responsible.

- In McNally's Dilemma (1999) by Lawrence Sanders and Vincent Lardo, McNally the narrator uses the phrase when a married with a step-daughter playboy George is found murdered. George's reputation was well known in West palm beach Florida and many including his wife would've argued that he got what he deserved.

- In Lonely Road (1932) by Nevil Shute, when the hero, Stevenson, confronts the plot mastermind, Ormsby, and consequently Ormby realises that his game is up and his only way out is suicide, quoting the phrase.

Short stories

[edit]- In "De Mortuis" (1942), by John Collier, after an unwitting cuckold is accidentally informed of his wife's infidelities, he plans an opportunistic revenge; the titular phrase, de mortuis, implies the murderous ending of the story.

- In "What the Dead Men Say" (1964), by Philip K. Dick, after the main character has spoken ill of his recently deceased boss, his wife tells him "Nil nisi bonum", then explaining to her bamboozled husband that it comes from the classic cartoon "Bambi". It might be used to suggest the confusion of cultural references in this story's world set in approximately 2075.

- In "EPICAC", by Kurt Vonnegut, after the demise of his friend/project, EPICAC, the supercomputer, the protagonist states the phrase in a memoir of someone who has done great for him.

Poetry

[edit]

- In "Sunlight on the Sea" (The Philosophy of a Feast), by Adam Lindsay Gordon, the mortuary phrase is the penultimate line of the eighth, and final, stanza of the poem.

Philosophy

[edit]

- In Thoughts for the Times on War and Death (1915), Sigmund Freud denounced the cultural stupidity that was the First World War (1914–18); yet, in the essay "Our Attitude Towards Death", recognised the humanity of the participants, and the respect owed them in the mortuary phrase De mortuis nil nisi bene.

Cinema

[edit]- In the war–adventure film Lawrence of Arabia (1962), the phrase is cautiously used at the funeral of T. E. Lawrence, officiated at St Paul's Cathedral; two men, a clergyman and a soldier, Colonel Brighton, are observing a bust of the dead "Lawrence of Arabia", and commune in silent mourning. The clergyman asks: "Well, nil nisi bonum. But did he really deserve . . . a place in here?" Colonel Brighton's reply is a pregnant silence.

Theatre

[edit]

- In The Seagull (1896), by Anton Chekhov, a character mangles the mortuary phrase, conflating it with the maxim De gustibus non est disputandum ("About taste there is no disputing"), which results in the mixed mortuary opinion: De gustibus aut bene, aut nihil ("Let nothing be said of taste, but what is good").[2]

- In Julius Caesar (1599) by William Shakespeare, Mark Antony uses what is possibly a perverted form of the phrase De mortuis nil nisi bonum, when he says: "The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones..."[3]

In other languages

[edit]Other languages have expressions that have a similar meaning. For example, in Hebrew, one might use אחרי מות קדושים אמור (Aḥare mot k'doshim emor), which may be translated into: "After the death, say 'they were holy'". The expression is formed by names of three consecutive sedras in Leviticus: Acharei Mot, Kedoshim and Emor, and has been taken to mean that one should not speak ill of the dead.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Traversari, Ambrogio (1432). Benedictus Brognolus (ed.). Laertii Diogenis vitae et sententiae eorvm qvi in philosophia probati fvervnt (in Latin). Venice: Impressum Venetiis per Nicolaum Ienson gallicum. Retrieved 12 May 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chekhov, Anton (1997). The Seagull. Translated by Stephen Mulrine. London: Nick Hern Books Ltd. pp. Introduction, p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-85459-193-7.

- ^ Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar.