A. P. J. Abdul Kalam

A. P. J. Abdul Kalam | |

|---|---|

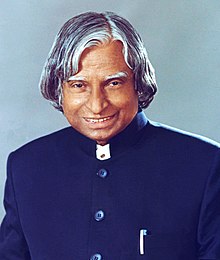

Official portrait, 2002 | |

| President of India | |

| In office 25 July 2002 – 25 July 2007 | |

| Prime Minister | Atal Bihari Vajpayee Manmohan Singh |

| Vice President | Krishan Kant Bhairon Singh Shekhawat |

| Preceded by | K. R. Narayanan |

| Succeeded by | Pratibha Patil |

| Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India | |

| In office November 1999 – November 2001 | |

| President | K. R. Narayanan |

| Prime Minister | Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Rajagopala Chidambaram |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 October 1931 Rameswaram, Madras Presidency, British India (modern–day Tamil Nadu, India) |

| Died | 27 July 2015 (aged 83) Shillong, Meghalaya, India |

| Resting place | Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Memorial, Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Political party | Independent[1] |

| Alma mater | |

| Profession | |

| Awards | List of awards and honours |

| Notable work(s) | |

| Signature | |

| Website | A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Centre |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Aerospace engineering |

| Institutions | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

(2002-2007) Books and publications Associated projects

Gallery: Picture, Sound, Video |

||

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam (/ˈəbdʊl kəˈlɑːm/ ⓘ; 15 October 1931 – 27 July 2015) was an Indian aerospace scientist and statesman who served as the president of India from 2002 to 2007.

Born and raised in a Muslim family in Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu, he studied physics and aerospace engineering. He spent the next four decades as a scientist and science administrator, mainly at the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and was intimately involved in India's civilian space programme and military missile development efforts. He was known as the "Missile Man of India" for his work on the development of ballistic missile and launch vehicle technology. He also played a pivotal organisational, technical, and political role in India's Pokhran-II nuclear tests in 1998, the second test since the first nuclear test by India in 1974.

Kalam was elected as the president of India in 2002 with the support of both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and the then-opposition Indian National Congress. He was widely referred to as the "People's President". He engaged in teaching, writing and public service after his presidency. He was a recipient of several awards, including the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour.

While delivering a lecture at IIM Shillong, Kalam collapsed and died from an apparent cardiac arrest on 27 July 2015, aged 83. Thousands attended the funeral ceremony held in his hometown of Rameswaram, where he was buried with full state honours. A memorial was inagurated near his home town in 2017.

Early life and education

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam was born on 15 October 1931, to a Tamil Muslim family in the pilgrimage centre of Rameswaram on Pamban Island, Madras Presidency (now in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu).[2][3] His father Jainulabdeen Marakayar was a boat owner and imam of a local mosque,[4] and his mother Ashiamma was a housewife.[5][6] His father owned a boat that ferried Hindu pilgrims between Rameswaram and Dhanushkodi.[7][8]

Kalam was the youngest of four brothers and a sister in the family.[9][10][11] His ancestors had been wealthy Marakayar traders and landowners, with numerous properties and large tracts of land. Marakayar are a Muslim ethnic group found in coastal Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka who claim descent from Arab traders and local women. The family business had involved trading goods and transporting passengers between the Indian mainland and the Pamban island and to and from Sri Lanka. With the opening of the Pamban Bridge connecting Pamban island to mainland India in 1914, the businesses failed. As a result, apart from the ancestral home, the other family fortune and properties were lost by the 1920s, and the family was poverty-stricken by the time Kalam was born. As a young boy, he delivered newspapers to support the family's meager income.[12][13][14]

In his school years, Kalam got average grades but was described as a bright and hardworking student and someone with a strong desire to learn by his teachers. He spent hours on learning mathematics.[14] He completed his school education at Schwartz Higher Secondary School in Ramanathapuram, and later graduated in physics from the St. Joseph's College in Tiruchirappalli in 1954.[15]

Kalam moved to Madras in 1955 to study aerospace engineering at the Madras Institute of Technology.[3] While he was working on a class project, the Dean of the institution was dissatisfied with his lack of progress and threatened to revoke his scholarship unless the project was finished within the next three days. Kalam met the deadline, impressing the Dean, who later said to him, "I was putting you under stress and asking you to meet a difficult deadline."[16] Later, he narrowly missed out on his dream of becoming a fighter pilot, as he placed ninth in qualifiers, and only eight positions were available in the Indian Air Force.[17]

Career as a scientist

This was my first stage, in which I learnt leadership from three great teachers—Dr Vikram Sarabhai, Prof Satish Dhawan and Dr Brahm Prakash. This was the time of learning and acquisition of knowledge for me.

After graduating from the Madras Institute of Technology in 1960, Kalam became a member of the Defence Research & Development Service and joined the Aeronautical Development Establishment of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) as a scientist. During his early career, he was involved in the design of small hovercraft, and remained unconvinced by his choice of a job at DRDO.[19] Later, he joined the Indian National Committee for Space Research, working under renowned space scientist Vikram Sarabhai.[3] He was interviewed and recruited into Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) by H. G. S. Murthy, the first director of the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station.[20]

In 1969, Kalam transferred to ISRO where he became the project director of India's first satellite launch vehicle (SLV) which successfully deployed the Rohini satellite in near-earth orbit in July 1980. He had earlier started work on an expandable rocket project independently at DRDO in 1965.[21] In 1969, Kalam received the approval from the Government of India to expand the programme to include more engineers.[18] In 1963-64, he visited NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, and Wallops Flight Facility.[2][22] Since the late 1970s, Kalam was part of the effort to develop the SLV-3 and Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), both of which were successful.[23][24]

In May 1974, Kalam was invited by Raja Ramanna to witness the country's first nuclear test Smiling Buddha as the representative of Terminal Ballistics Research Laboratory, even though he was officially not part of the project.[25] In the 1970s, Kalam directed two projects, Project Devil and Project Valiant, which sought to develop ballistic missiles using the technology from the successful SLV programme. Despite the disapproval of the union cabinet, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi allotted funds for these aerospace projects under Kalam's directorship through her discretionary powers. Kalam also played a major role in convincing the cabinet to conceal the true nature of these classified projects. His research and leadership brought him recognition in the 1980s, which prompted the government to initiate an advanced missile programme under his directorship.[26]

Kalam worked with metallurgist V. S. R. Arunachalam, who was then scientific adviser to the Defence Minister, on the suggestion by the then Defence Minister R. Venkataraman on the simultaneous development of a quiver of missiles instead of taking planned missiles one after another.[27] Venkatraman was instrumental in getting the cabinet approval for allocating ₹3.88 billion (equivalent to ₹66 billion or US$760 million in 2023) for the project titled Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme (IGMDP) and appointed Kalam as its chief executive.[27] Kalam played a major role in the development of missiles including Agni, an intermediate range ballistic missile and Prithvi, the tactical surface-to-surface missile, despite inflated costs and time overruns.[27][28] He was known as the "Missile Man of India" for his work on the development of ballistic missile and launch vehicle technology.[29][30][31]

Kalam served as the chief scientific adviser to the prime minister and secretary of the DRDO from July 1992 to December 1999. He played a key organisational, political and techinical role in the Pokhran-II nuclear tests conducted in May 1998.[32] Along with Rajagopala Chidambaram, he served as the chief project coordinator for the tests.[2][33] Media coverage of Kalam during this period made him the country's best known nuclear scientist.[34] However, the director of the site test, K. Santhanam, said that the thermonuclear bomb had been a "fizzle" and criticised Kalam for issuing an incorrect report.[35] The claim was refuted and rejected by Kalam and Chidambaram.[36]

In 1998, Kalam worked with cardiologist Bhupathiraju Somaraju and developed a low cost coronary stent, named the "Kalam-Raju stent".[37][38] In 2012, the duo designed a tablet computer named the "Kalam-Raju tablet" for usage by healthcare workers in rural areas.[39]

Presidency

On 10 June 2002, the National Democratic Alliance which was in power at the time, expressed its intention to nominate Kalam for the post of the President of India.[40][41] His candidature was backed by the opposition parties including the Samajwadi Party and the Nationalist Congress Party.[42][43] After the support for Kalam, incumbent president K. R. Narayanan chose not to seek a re-election.[44] Kalam said of the announcement of his candidature:

I am really overwhelmed. Everywhere both in Internet and in other media, I have been asked for a message. I was thinking what message I can give to the people of the country at this juncture.[45]

On 18 June, Kalam filed his nomination papers in the Indian Parliament, accompanied by then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and senior cabinet members.[46] He faced off against Lakshmi Sahgal, and the polling for the presidential election was held on 15 July 2002, in the Indian parliament and the state assemblies, with the media predicting a win for Kalam.[47] The counting was held on 18 July, and Kalam won the elections after securing 922,884 electoral votes as against the 107,366 votes won by Sahgal.[48] He was sworn in as the 11th president of India on 25 July 2002.[49][50] He was the first scientist and the first bachelor to occupy the top chair at Rashtrapati Bhawan.[51]

During his term as president, he was affectionately known as the "People's President".[52][53][54][55] He later stated that signing the Office of profit bill was the toughest decision he had taken during his tenure.[56][57][58] In September 2003, during an interactive session at PGIMR in Chandigarh, Kalam asserted the need of Uniform Civil Code in India, keeping in view the population of the country.[59][60] He also took a decision to impose President's rule in Bihar in 2005.[61] However, during his tenure as president, he made no decision on 20 out of the 21 mercy petitions submitted to him to commute death penalties, including that of terrorist Afzal Guru, who was convicted of conspiracy in the December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament and was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of India in 2004.[62] He acted only on a single plea, rejecting that of Dhananjoy Chatterjee, who was later hanged.[63]

Towards the end of his term, on 20 June 2007, Kalam expressed his willingness to consider a second term in office provided there was certainty about his victory in the upcoming presidential election.[64] His name was proposed by the United National Progressive Alliance, but he did receive the support of the ruling United Progressive Alliance.[65][66] However, two days later, he decided not to contest the election again stating that he wanted to avoid involving the Rashtrapati Bhavan in the political processes.[67]

In April 2012, towards the expiry of the term of the 12th president Pratibha Patil, media reports claimed that Kalam was likely to be nominated for his second term.[68][69][70] After the reports, social networking sites witnessed a surge in posts supporting his candidature.[71][72] While the ruling Indian National Congress opposed the nomination of Kalam,[73] other parties such as the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Trinamool Congress were reported by the media to be keen on his candidature.[74][75][76][77] On 18 June 2012, Kalam declined to contest stating that:

Many, many citizens have also expressed the same wish. It only reflects their love and affection for me and the aspiration of the people. I am really overwhelmed by this support. This being their wish, I respect it. I want to thank them for the trust they have in me.[78]

Post-presidency

After leaving office, Kalam returned to teaching, and became a visiting professor at various institutions. He became a visiting professor at IIM Shillong,[79] a honorary professor at his alma mater Anna University in Chennai,[80] and a honorary fellow of the Indian Institute of Science at Bengaluru.[81][82] He also conducted lectures for management students in India,[83] and visited China twice at the invitation of the Chinese government to conduct sessions at the Peking University.[84]

In 2011, Kalam voiced his support towards the establishment of the nuclear power plant at Koodankulam in Tamil Nadu, giving assurances for the safety of the facility.[85] However, some of the locals were unconvinced by his statements on the safety of the plant, and were hostile to his visit.[86] In May 2012, Kalam launched a programme called What Can I Give Movement aimed at the youth of India with a central theme of defeating corruption.[87][88]

Death

On 27 July 2015, Kalam travelled to Shillong to deliver a lecture on "Creating a Livable Planet Earth" at IIM Shillong. While climbing a flight of stairs, he experienced some discomfort, but was able to enter the auditorium after a brief rest.[89][90] At around 6:35 p.m. IST, after five minutes into his lecture, he collapsed.[91] He was rushed to the nearby Bethany Hospital in a critical condition, and upon arrival, he lacked a pulse or any other signs of life. Despite being placed in the intensive care unit, he was confirmed dead of a sudden cardiac arrest at 7:45 p.m.[92][93] His purported last words to his aide Srijan Pal Singh were: "Funny guy! Are you doing well?"[94]

Following his death, Kalam's body was flown to New Delhi on the morning of 28 July, where dignitaries including then president, vice president, and prime minister paid their last respects.[95] His body was placed in his Delhi residence for public viewing.[96] 29 July, his body was flown to the town of Mandapam via Madurai, and carried onwards towards his home town of Rameswaram by road. His body was displayed in an open area to allow the public to pay their final respects until 8 p.m. that evening.[97][98][99] On 30 July 2015, the former president was laid to rest at Rameswaram's Pei Karumbu ground with full state honours with over 350,000 people in attendance.[100][101]

Memorial

A memorial was built in memory of Kalam by the DRDO in Pei Karumbu in Rameswaram.[102] It was inaugurated by then prime minister Narendra Modi in July 2017.[103][104] The memorial displays replicas of rockets and missiles which Kalam had worked with, and various acrylic paintings about his life. There is a large statue of Kalam in the entrance showing him playing the veena, and two other smaller statues in sitting and standing posture respectively.[105]

Personal life and interests

Kalam was the youngest of five siblings, the eldest of whom was a sister, Asim Zohra (d. 1997), followed by three elder brothers: Mohammed Lebbai (5 November 1916–7 March 2021),[106][107] Mustafa Kalam (d. 1999) and Kasim Mohammed (d. 1995).[108] He was close to his elder siblings and their extended families throughout his life, and would regularly send small sums of money to his older siblings, though he himself remaining a lifelong bachelor.[108][109]

Kalam was noted for his integrity and his simple lifestyle.[109][110] He was a teetotaler,[111] and a vegetarian.[112] Kalam enjoyed writing Tamil poetry, playing the veena (an Indian string instrument),[113] and listening to Carnatic devotional music every day.[114] He never owned a television, and was in the habit of rising at 6:30 or 7 a.m. and sleeping by 2 a.m.[115] His personal possessions included a few books, a veena, clothing, a compact disc player and a laptop. He left no will, and his possessions went to his eldest brother after his death.[116][117]

Kalam set a target of interacting with 100,000 students during the two years after his resignation from the post of scientific adviser in 1999. He explained, "I feel comfortable in the company of young people, particularly high school students. Henceforth, I intend to share with them experiences, helping them to ignite their imagination and preparing them to work for a developed India for which the road map is already available." His dream is to let every student to light up the sky with victory using their latent fire in the heart.[118] He had an active interest in other developments in the field of science and technology such as developing biomedical implants. He also supported open source technology over proprietary software, predicting that the use of free software on a large scale would bring the benefits of information technology to more people.[119]

Religious and spiritual views

Religion and spirituality were very important to Kalam throughout his life.[120] He was a practising Sunni Muslim, and daily namaz and fasting during Ramadan were integral to his life.[114][121] His father was an imam of a mosque, and had strictly instilled these Islamic customs in his children.[4] His father had also impressed upon the young Kalam the value of interfaith respect and dialogue. As Kalam recalled: "Every evening, my father A. P. Jainulabdeen, an imam, Pakshi Lakshmana Sastry, the head priest of the Ramanathaswamy Hindu temple, and a church priest used to sit with hot tea and discuss the issues concerning the island."[122][123] Such early exposure convinced Kalam that the answers to India's multitudinous issues lay in "dialogue and cooperation" among the country's religious, social, and political leaders.[121] Moreover, since Kalam believed that "respect for other faiths" was one of the key cornerstones of Islam, and he remarked: "For great men, religion is a way of making friends; small people make religion a fighting tool."[124]

One component of Kalam's widespread popularity among diverse groups in India, and an enduring aspect of his legacy, is the syncretism he embodied in appreciating various elements of the many spiritual and cultural traditions of India.[114][121][125] In addition to his faith in the Quran and Islamic practice, Kalam was well-versed in Hindu traditions, learnt Sanskrit.[126][127] and read the Bhagavad Gita.[128][129] In 2002, in one of his early speeches to Parliament after becoming the president, he reiterated his desire for a more united India, stating that "During the last one year I met a number of spiritual leaders of all religions ... and I would like to endeavour to work for bringing about unity of minds among the divergent traditions of our country".[125] Describing Kalam as a unifier of diverse traditions, Shashi Tharoor remarked, "Kalam was a complete Indian, an embodiment of the eclecticism of India's heritage of diversity".[114] Former deputy prime minister L. K. Advani concurred that Kalam was "the best exemplar of the Idea of India, one who embodied the best of all the cultural and spiritual traditions that signify India's unity in immense diversity.[130]

Kalam's desire to meet spiritual leaders led him to meet Pramukh Swami Maharaj, the Hindu guru of the Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS), who Kalam would come to consider his ultimate spiritual teacher and guru.[121] Kalam and Pramukh Swami met eight times over a fourteen-year period and on his first meeting on 30 June 2001, Kalam described being immediately drawn to Pramukh Swami's simplicity and spiritual purity.[122][131] Kalam stated that he was inspired by Pramukh Swami throughout their numerous interactions, and recalled being moved by Swami's equanimity and compassion, citing this incident as one of his motivations for writing his experiences as a book later.[122] Summarising the effect that Pramukh Swami had on him, Kalam stated that "[Pramukh Swami] has indeed transformed me. He is the ultimate stage of the spiritual ascent in my life ... Pramukh Swamiji has put me in a God-synchronous orbit. No manoeuvres are required any more, as I am placed in my final position in eternity."[121][132]

Writings

Kalam has authored various books during his career, and his books have garnered interest various countries.[133]

In his book India 2020, he strongly advocated an action plan to develop India into a "knowledge superpower" and a developed nation by 2020. He regarded his work on India's nuclear weapons programme as a way to assert India's place as a future superpower.[134]

I have identified five areas where India has a core competence for integrated action: (1) agriculture and food processing; (2) education and healthcare; (3) information and communication technology; (4) infrastructure, reliable and quality electric power, surface transport and infrastructure for all parts of the country; and (5) self-reliance in critical technologies. These five areas are closely inter-related and if advanced in a coordinated way, will lead to food, economic and national security.

Kalam described a "transformative moment" in his life in his book Transcendence: My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Swamiji. When he asked Pramukh Swami on how India might realise his vision of development, Swami answered to add a sixth area of developing faith in God and spirituality to overcome the current climate of crime and corruption.[122]

- Bibliography

- Developments in Fluid Mechanics and Space Technology by A P J Abdul Kalam and Roddam Narasimha; Indian Academy of Sciences, 1988.[135]

- India 2020: A Vision for the New Millennium by A P J Abdul Kalam, Y. S. Rajan; New York, 1998.[136]

- Wings of Fire: An Autobiography by A P J Abdul Kalam, Arun Tiwari; Universities Press, 1999.[2]

- Ignited Minds: Unleashing the Power Within India by A P J Abdul Kalam; Viking, 2002.[137]

- The Luminous Sparks by A P J Abdul Kalam, by; Punya Publishing Pvt Ltd., 2004.[138]

- Mission India by A P J Abdul Kalam, Paintings by Manav Gupta; Penguin Books, 2005[139]

- Inspiring Thoughts by A P J Abdul Kalam; Rajpal & Sons, 2007[140]

- Indomitable Spirit by A P J Abdul Kalam; Rajpal & Sons Publishing[141]

- Envisioning an Empowered Nation by A P J Abdul Kalam with A Sivathanu Pillai; Tata McGraw-Hill, New Delhi[142]

- You Are Born To Blossom: Take My Journey Beyond by A P J Abdul Kalam and Arun Tiwari; Ocean Books, 2011.[143]

- Turning Points: A journey through challenges by A P J Abdul Kalam; HarperCollins India, 2012.[144]

- Target 3 Billion by A P J Abdul Kalam and Srijan Pal Singh; December 2011 (Publisher: Penguin Books).

- My Journey: Transforming Dreams into Actions by A P J Abdul Kalam; 2014 by the Rupa Publication.[145]

- A Manifesto for Change: A Sequel to India 2020 by A P J Abdul Kalam and V Ponraj; July 2014 by HarperCollins.[146]

- Forge your Future: Candid, Forthright, Inspiring by A P J Abdul Kalam; by Rajpal & Sons, 29 October 2014.[147]

- Reignited: Scientific Pathways to a Brighter Future by A P J Abdul Kalam and Srijan Pal Singh; by Penguin India, 14 May 2015.[148]

- Transcendence: My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Swamiji by A P J Abdul Kalam with Arun Tiwari; HarperCollins Publishers, June 2015[149]

- Advantage India: From Challenge to Opportunity by A P J Abdul Kalam and Srijan Pal Singh; HarperCollins Publishers,15 October 2015.[150]

Awards and honours

Kalam received honorary doctorates from various universities.[151][152][153] The Government of India honoured him with the Padma Bhushan in 1981 and the Padma Vibhushan in 1990.[25] In 1997, he was awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, for his contribution to the scientific research and modernisation of defence technology in India.[154] He received the Indira Gandhi Award for National Integration in 1997, and Ramanujan Award in 2000.[25] In 2008, he was the recipient of Hoover Medal.[155] In 2013, he was awarded the Von Braun Award by the National Space Society "to recognize excellence in the management and leadership of a space-related project".[156]

Legacy

The Government of Tamil Nadu announced that his birthday, 15 October, would be observed across the state as "Youth Renaissance Day;" the state government further instituted the "Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Award", constituting an 8-gram gold medal, a certificate and ₹500,000 (US$5,800). The award will be awarded annually on Independence Day, beginning in 2015, to residents of the state with achievements in promoting scientific growth, the humanities or the welfare of students.[157] In 2012, Kalam was ranked second in the Greatest Indian poll conducted by Outlook.[158] On the anniversary of Kalam's birth in 2015 the CBSE set topics on his name in the CBSE expression series.[159] Prime Minister Narendra Modi ceremonially released postage stamps commemorating Kalam at DRDO Bhawan in New Delhi on 15 October 2015, the 84th anniversary of Kalam's birth.[citation needed]

Researchers at the NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory had discovered a new bacterium on the filters of the International Space Station and named it Solibacillus kalamii to honour Kalam.[160] In February 2018, scientists from the Botanical Survey of India named a newly found plant species as Drypetes kalamii, in his honour.[161] In 2022 a newly discovered species of footballfish, Himantolophus kalami was named in Kalam's honour.[162]

Wheeler Island, a national missile test site in Odisha, was renamed Abdul Kalam Island in September 2015.[163] A prominent road in New Delhi was renamed from Aurangzeb Road to Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Road[164][165] in August 2015.[166] Several educational and scientific institutions and other locations were renamed or named in honour of Kalam following his death.

- Kerala Technological University, headquartered at Thiruvananthapuram where Kalam lived for years, was renamed to A P J Abdul Kalam Technological University after his death.

- An agricultural college at Kishanganj, Bihar, was renamed the "Dr. Kalam Agricultural College, Kishanganj" by the Bihar state government on the day of Kalam's funeral. The state government also announced it would name a proposed science city after Kalam.[167]

- India's First Medical Tech Institute named as Kalam Institute of Health Technology located at Visakhapatnam.[168]

- Uttar Pradesh Technical University (UPTU) was renamed A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Technical University by the Uttar Pradesh state government.[169]

- A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Memorial Travancore Institute of Digestive Diseases, a new research institute in Kollam city, Kerala attached to the Travancore Medical College Hospital.[170]

- A new academic complex at Mahatma Gandhi University in Kerala.[171]

- Construction of Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Science City started in Patna in February 2019.[172]

- A new science centre and planetarium in Lawspet, Puducherry.[173]

- India and the US have launched the Fulbright-Kalam Climate Fellowship in September 2014. The first call for applicants was announced on Friday, 12 March 2016, for the fellowship which will enable up to 6 Indian PhD students and post-doctoral researchers to work with US host institutions for a period of 6–12 months. The fellowship will be operated by the binational US-India Educational Foundation (USIEF) under the Fulbright programme.[174]

- Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Planetarium in Burla, Sambalpur, Odisha was named after him.

- Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Lecture Theatre Complex at Netaji Subhas University of Technology.[175]

In popular culture

- Biographies

- Eternal Quest: Life and Times of Dr Kalam by S Chandra; Pentagon Publishers, 2002.[176]

- President A P J Abdul Kalam by R K Pruthi; Anmol Publications, 2002.[177]

- A P J Abdul Kalam: The Visionary of India by K Bhushan, G Katyal; A P H Pub Corp, 2002.[178]

- A Little Dream (documentary film) by P. Dhanapal; Minveli Media Works Private Limited, 2008.[179]

- The Kalam Effect: My Years with the President by P M Nair; HarperCollins, 2008.[180]

- My Days With Mahatma Abdul Kalam by Fr A K George; Novel Corporation, 2009.[181]

- A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: A Life by Arun Tiwari; Harper Collins, 2015.[182]

- The People's President: Dr A P J Abdul Kalam by S M Khan; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.[183]

- Popular culture

- In the 2011 Hindi film I Am Kalam, Kalam is portrayed as a positive influence on a poor but bright Rajasthani boy named Chhotu, who renames himself Kalam in honour of his idol.[184] My Hero Kalam is a 2018 Indian Kannada-language biographical film by Shivu Hiremath which portrays his life from childhood to the Pokhran tests.[185]

- People's President is a 2016 Indian documentary feature film directed by Pankaj Vyas which covers the life of Kalam. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.[186]

- Mega Icons (2018–2020), a documentary television series about prominent personalities of India which aired on National Geographic, based the third episode – "APJ Abdul Kalam" – on Kalam's life and his ascendancy to India's presidency.[187]

- Soorarai Pottru, a 2020 film about the Indian aviation industry had a look-alike of Kalam, Sheik Maideen, portraying him.[188]

- Rocket Boys[189], an Indian Hindi-language Biographical streaming television series on SonyLIV. The character of Kalam was played by Arjun Radhakrishnan.

- Rocketry: The Nambi Effect, a 2022 film about ISRO espionage case, Abdul Kalam's character is portrayed by actor Amaan.[190]

See also

References

- Footnotes

- Citations

- ^ Appointed for 2002 Presidential Elections as an Independent Candidate; in coalition with NDA, during Vajpayee Government

- ^ a b c d Kalam, Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul; Tiwari, Arun (1999). Wings of Fire: An Autobiography. Universities Press. ISBN 978-81-7371-146-6. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Bio-data: Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b Akbar, M J (9 July 2012). "APJ Abdul Kalam speaks to Editorial Director M.J. Akbar about presidential elections 2012". India Today. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Dr Abdul Kalam, People's President in Sri Lanka". Daily News. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Jai, Janak Raj (2003). Presidents of India, 1950–2003. Regency Publications. p. 296. ISBN 978-81-87498-65-0. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam, the unconventional President who learnt the art of the political". ABP News. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "The greatest student India ever had". Dailyo. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Brother awaits Kalam last trip". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "How two orthodox Brahmins played a crucial role in APJ Abdul Kalam's childhood". Qz. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Day before death, Kalam enquired about elder brother's health". IBN Live. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Not aware of any will left by Kalam: nephew". The Times of India. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Sharma, Mahesh; Das, P.K.; Bhalla, P. (2004). Pride of the Nation: Dr. A.P.J Abdul Kalam. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-288-0806-7. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

visitwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ K. Raju; S. Annamalai (24 September 2006). "Kalam meets the teacher who moulded him". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ Dixit, Sumita Vaid (18 March 2010). "The boy from Rameswaram who became a President". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "Failed in my dream of becoming a pilot : Abdul Kalam in new book". The Hindu. 18 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Gopalakrishnan, Karthika (23 June 2009). "Kalam tells students to follow their heart". The Times of India. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Pawar, Ashwini (29 July 2015). "I'm proud that I recommended him for ISRO: EV Chitnis". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Ramchandani (2000). Dale Hoiberg (ed.). A to C (Abd Allah ibn al-Abbas to Cypress). New Delhi: Encyclopædia Britannica (India). p. 2. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Science and Public Affairs. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science: 32. November 1989. ISSN 0096-3402. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "When Dr APJ Abdul Kalam learnt from failure and Isro bounced back to life". India Today. 23 August 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam, profile". Rashtrapathi Bhavan. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Lesser Known Facts About Dr APJ Abdul Kalam". The New Indian Express. 28 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Missile Chronology, 1971–1979" (PDF). James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at Monterey Institute of International Studies, Nuclear Threat Initiative. July 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "The prime motivator". Frontline. 5 July 2002. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Pandit, Rajat (9 January 2008). "Missile plan: Some hits, misses". The Times of India. TNN. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Pruthi, R. K. (2005). "Missile Man of India". President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. Anmol Publications. pp. 61–76. ISBN 978-81-261-1344-6. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "India's 'Mr. Missile': A man of the people". Toronto Sun. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Kalam's unrealised 'Nag' missile dream to become reality next year". The Times of India. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Sen, Amartya (2003). "India and the Bomb". In M. V. Ramana; C. Rammanohar Reddy (eds.). Prisoners of the Nuclear Dream. Sangam Books. pp. 167–188. ISBN 978-81-250-2477-4. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Jerome M. Conley (2001). Indo-Russian military and nuclear cooperation: lessons and options for U.S. policy in South Asia. Lexington Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7391-0217-6. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "Koodankulam nuclear plant: A. P. J. Abdul Kalam's safety review has failed to satisfy nuke plant protestors, expert laments". The Economic Times. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ R., Ramachandran (25 September 2009). "Pokhran row". Frontline. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Hardnews bureau (August 2009). "Pokhran II controversy needless: PM". Hard News. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Story of indigenous stents". Business Line. India. 15 August 2001. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012.

- ^ "The stent man". Rediff.com. India. 19 December 1998. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013.

- ^ Gopal, M. Sai (22 March 2012). "Now, 'Kalam-Raju tablet' for healthcare workers". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Times News Network (11 June 2002). "NDA's smart missile: President Kalam". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "With him at the helm, there is hope that things might change". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015.

- ^ "SP to support Kalam for President's post". Rediff.com. 11 June 2002. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "NCP supports Kalam's candidature for presidentship". Rediff.com. 11 June 2002. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Narayanan opts out, field clear for Kalam". Rediff.com. 11 June 2002. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Overwhelmed by response: Kalam". Rediff.com. 13 June 2002. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Presidential nominee Abdul Kalam files nomination papers". Rediff.com. 18 June 2002. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Polling for presidential election begins". Rediff.com. 15 July 2002. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Ved, Mahendra (26 July 2002). "Kalam is 11th President in 12th term". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "Former Presidents, Rashtrapati Bhavan". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Abdul Kalam elected President". The Hindu. 18 July 2002. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "A P J Kalam is sworn in as India's eleventh President". Rediff.com. 25 July 2002. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Tyagi, Kavita; Misra, Padma (23 May 2011). Basic Technical Communication. Prentice Hall. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-203-4238-5. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Amarnath Menon (28 July 2015). "Why Abdul Kalam was the 'People's President'". DailyO. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam is people's president: Mamata Banerjee". CNN-IBN. Press Trust of India. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Perappadan, Bindu Shajan (14 April 2007). "The people's President does it again". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "My toughest decision as president was returning the Office of Profit Bill to Parliament". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "How a 110 years old became friend of APJ Kalam". Better India. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Signing office of profit bill was toughest decision: A P J Kalam". The Economic Times. 18 July 2010. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Uniform Civil Code essential: Kalam". Rediff.com. 29 September 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Kalam calls for uniform civil code". The Economic Times. 30 September 2003. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam: The People's President". NDTV. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ V., Venkatesan (April 2009). "Mercy Guidelines". Frontline. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ "The journey of a mercy plea". The New Indian Express. 21 May 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ "Kalam not to contest presidential poll". Rediff.com. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Kalam not to contest Presidential polls". The Times of India. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Talks under way on Presidential election". The Hindu. 10 May 2007. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Kalam not to contest Presidential polls". The Times of India. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Raj, Rohit (23 April 2012). "Virtual world seeks second term for Abdul Kalam". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Prafulla Marapakwar (23 April 2012). "Next President should be apolitical: Pawar". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Race for Rashtrapati Bhawan: APJ Abdul Kalam a good choice, says SP; backs Pawar". NDTV. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Netizens campaign for second term to Kalam". Deccan Herald. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Azeez, Parwin (8 May 2012). "Kalam for President clicks on social networks". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Benedict, Kay (14 June 2012). "Congress opposes APJ Abdul Kalam's name for President". India Today. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "President poll: BJP rejects Pranab Mukherjee, Hamid Ansari, may back Kalam". CNN-IBN. New Delhi. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Presidential polls: We will not support Pranab Mukherjee, BJP says". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Prez poll: Mulayam, Mamata suggest APJ Kalam, Manmohan Singh, Somnath Chatterjee". DNA India. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Mamata turns to Facebook, seeks support for Kalam". The Times of India. Kolkata, India. Press Trust of India. 16 June 2012. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Karthick S (18 June 2012). "Abdul Kalam not to contest presidential poll 2012". The Times of India. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Kalam to join as visiting faculty at IIM Shillong". Dinamalar (in Tamil). 7 March 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Kalam may become honorary professor". The Hindustan Times. 15 July 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Honorary Fellowship of IISc". Indian Institute of Science. 27 May 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Kalam, Abdul (22 June 2012). Turning Points: A Journey Through Challenges. Harper Collins (published 5 September 2012). pp. 48, 69. ISBN 978-9-35029-543-4. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Kalam to teach management students". The Economic Times. 22 December 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "China professor: Abdul Kalam not just India's scientist but of the world". The Indian Express. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Dr Kalam's 'assurance' on nuclear power plants draws flak". Financial Magazine. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Kalam bats for Kudankulam but protesters unimpressed". The Times of India. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ "About us". What Can I Give. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Mallady, Shastry (26 June 2011). "Take part in movement against corruption: Kalam". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Scott, D.J. Walter (3 August 2015). "Kalam had no property". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "End of an era: 'Missile man' APJ Abdul Kalam passes away after cardiac arrest". Firstpost. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Abdul Kalam, former president of India, passes away at 84". The Indian Express. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ "Abdul Kalam showed no signs of life when brought to hospital: Doctor". CNN-IBN. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Anindita Sanyal (27 July 2015). "Former President APJ Abdul Kalam Dies at 83". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "11 Last Words of Famous People That Reflect Exactly What Life Was To Them". India Times. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Farewell Kalam! Pranab, Modi lead nation in paying homage". The Hindustan Times. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Live: Kalam's body at Delhi house for people to pay tribute". India Today. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Arunachalam, Pon Vasanth (29 July 2015). "Dignitaries Pay Respect to Kalam in Madurai Airport". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Kalam's mortal remains reach Rameswaram". The Hindu. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Rishi Iyengar (28 July 2015). "India Pays Tribute to 'People's President' A.P.J. Abdul Kalam". Time Inc. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "People's president' Kalam laid to rest with full state honours". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Nation bids adieu to Abdul Kalam". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Dr APJ Abdul Kalam National Memorial Foundation Stone Laying Ceremony". Press Information Bureau. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016.

- ^ "Images of the Inauguration function". Defence Research and Development Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ "The Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi's web page with news and photos". Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ "What is the Abdul Kalam memorial row?". The Indian Express. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ "Kalam's elder brother dies at 104". The Hindu. 7 March 2021. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Abdul Kalam's elder brother turns 100 and APJ had bought a gift for him". India Today. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b "We thought he would be with us for another decade: Kalam's nephew". Mid-Day. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Man of integrity, Kalam insulated family from trappings of power". The Times of India. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Scott, Walter (4 November 2016). "Kalam's brother turns 100, says takes life as it comes". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

Kalam never accepted gifts when he attended functions...

- ^ Michael, Saneesh (n.d.). "A.P.J. Abdul Kalam - The President of the masses". OneIndia. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007.

- ^ "Of Rasam and Rice: The Humble Lifestyle of Former President Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam". NDTV. president-dr-apj-abdul-kalam-1201369 Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help) - ^ "India's A.P.J. Abdul Kalam". Time. 30 November 1998. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d Shashi Tharoor (28 June 2015). "Abdul Kalam: People's president, extraordinary Indian". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Kalam Tribute: Sir Never Had a TV at Home, Recalls Secretary of 24 Years". NDTV. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Kalam had no property". The Hindu. 3 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Guru Kalam's assets, royalties to go to elder brother". One India. 3 August 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Bhushan, K.; Katyal, G. (2002). A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: The Visionary of India. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 1–10, 153. ISBN 978-81-7648-380-3. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Becker, David (29 May 2003). "India leader advocates open source". CNET. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Lama, The Office of His Holiness the 14th Dalai. "The Office of His Holiness The Dalai Lama". www.dalailama.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Dr Kalam, India's Most Non-Traditional President". NDTV. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (2015). Transcendence: My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Swamiji. Noida: HarperCollins India. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 978-93-5177-405-1.

- ^ "Ramzan & Rameswaram: His ties with the island". The Times of India. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam: Not Hindu, Not Muslim – Death of an 'Indian'". 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Remembering Kalam: Greatly beloved, but he maybe missed being truly great". Firstpost. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Abdul Kalam or Abul Kalam- the message is same". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Kalam on why Sanskrit is important". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- ^ "Muslims react to A P J Abdul Kalam's candidature for President". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Three books that influenced APJ Abdul Kalam deeply". Firstpost. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Kalam served India till last breath: Advani". Zee News. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Transcending boundaries with Swamiji". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Did Kalam sense his end was near? Arun Tiwari suspects". The Hindu. 30 July 2015. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Kalam, the author catching on in South Korea". Outlook. 9 February 2006. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (1 October 2011). "IDG Session Address" (PDF). NUJS Law Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Developments in Fluid Mechanics and Space Technology". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul; Y.S., Rajan (1998). India 2020: A Vision for the New Millennium. New York. ISBN 978-0-670-88271-7. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (2002). Ignited minds: unleashing the power within India. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-04928-8. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (2004). The luminous sparks : a biography in verse and colours. Bangalore: Punya Pub. ISBN 978-81-901897-8-1.

- ^ Rajan, A.P.J. Abdul Kalam with Y.S. (2005). Mission India : a vision for Indian youth. New Delhi, India: Puffin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-333499-6.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (2007). Inspiring thoughts. Delhi: Rajpal & Sons. ISBN 978-81-7028-684-4.

- ^ Kalam, A.P.J. Abdul (2006). Indomitable Spirit. Delhi: Rajpal & Sons. ISBN 978-81-7028-654-7.

- ^ Kalam, Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul; Pillai, A. Sivathanu (2004). Envisioning an Empowered Nation: Technology for Societal Transformation. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-07-053154-3. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ You Are Born To Blossom : Take My Journey Beyond. New Delhi, India: Ocean Books. January 2010. ISBN 978-81-8430-037-6.

- ^ "Turning Points:A journey through challenges". HarperCollins India. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012.

- ^ Kalam, Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul (2014). My Journey: Transforming Dreams Into Actions. Rupa Publications India. ISBN 978-81-291-2491-3. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Dr. Abdul Kalam's new Book A Manifesto for Change to release on July 14". news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Abdul Kalam, A P J (29 October 2014). Forge Your Future: Candid, Forthright, Inspiring. Rajpal & Sons. ISBN 978-93-5064-279-5. ASIN 9350642794.

- ^ Abdul Kalam, A P J; Pal Singh, Srijan (14 May 2015). Reignited: Scientific Pathways to a Brighter Future. Penguin India. ISBN 978-0-14-333354-8. ASIN 0143333542.

- ^ Dr. Abdul Kalam's new Book Transcendence My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Swamiji to release on 15 June. HarperCollins India Publication. ASIN 9351774058.

- ^ A P J, Abdul Kalam; Srijan, Pal Singh (20 October 2015). Advantage India: From Challenge to Opportunity. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 978-9351776451.

- ^ "Dr.Kalam's Page". Abdulkalam.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Dayekh, Ribal (16 April 2011). "Dr Abdul Kalam former President of India arrives to Dubai". Zawya. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Kalam receives honorary doctorate from Queen's University Belfast". Oneindia.in. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Bharat Ratna conferred on Dr Abdul Kalam". Rediff.com. 26 November 1997. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam, 2008 Hoover Medal Recipient". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "NSS Von Braun Award". National Space Society. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Award in Kalam's name, birthday to be observed as 'Youth Renaissance Day'". Economic Times. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Sengupta, Uttam (20 August 2012). "A Measure of the Man". outlookindia.com/. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "APJ Abdul Kalam.pdf" (PDF). CBSE. 16 October 2015. pp. 1, 4–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "NASA pays tribute to APJ Abdul Kalam by naming new species after him". International Business Times. 21 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Pacha, Aswathi (24 February 2018). "New plant species from West Bengal named after former President Abdul Kalam". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Christopher Scharpf (3 June 2024). "Order LOPHIIFORMES (part 2): Families Caulophrynidae, Neoceratiidae, Melanocetidae, Himantolophidae, Diceratiidae, Oneirodidae, Thaumatichthyidae, Centrophrynidae, Ceratiidae, Gigantactinidae And Linophrynidaee". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. v. 3.0. Christopher Scharpf. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ "Odisha's Wheeler Island to be renamed after APJ Abdul Kalam". Hindustan Times. 4 September 2015. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Delhi exits 'cruel' Aurangzeb Road for 'kind' Abdul Kalam". 29 August 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Nath, Damini (4 September 2015). "Aurangzeb Road is now Abdul Kalam Road". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Aurangzeb Road Renamed After APJ Abdul Kalam, Arvind Kejriwal Tweets 'Congrats'". Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Bihar govt names college, science city after 'People's President' APJ Abdul Kalam". The Hindu. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "India's first medical tech institute". pharmabiz.com. 26 July 2017. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ "UPTU is now APJ Abdul Kalam Tech University". Times of India. 1 August 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Institute to be named after Kalam". The Hindu. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Complex to be named after Abdul Kalam". The Hindu. 4 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Rumi, Faryal (24 February 2019). "Work on APJ Abdul Kalam Science City to begin this month | Patna News – Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Science centre-cum-planetarium named after Abdul Kalam". The Hindu. 16 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "India, US Launch Fulbright-Kalam Climate Fellowship". Ndtv.com. 12 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "A university of technology embraces 'AV science' for technowledge dissemination". issuu.

- ^ Rohde, David (19 July 2002). "Nuclear Scientist, 70, a Folk Hero, Is Elected India's President". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ Pruthi, Raj (2003). President Apj Abdul Kalam. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-1344-6. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Bhushan, K.; Katyal, G. (2002). A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: The Visionary of India. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7648-380-3. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "Documentary on Kalam released". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 12 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ Nair, P. M. (2008). The Kalam Effect: My Years with the President. HarperCollins Publishers, a joint venture with the India Today Group. ISBN 978-81-7223-736-3. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Fr A K George (2009). My Days with Mahatma Abdul Kalam. Novel Corp. ISBN 978-81-904529-5-3. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Tiwari, Arun (2015). A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: A Life. HarperCollins. ISBN 9789351776918. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Khan, S M (2016). The People's President: Dr A P J Abdul Kalam. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9789386141521. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "I Am Kalam: Movie Review". The Times of India. 4 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "My Hero Kalam (2018)". Indiancine.ma. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Biopic to be streamed as tribute to Dr APJ Abdul Kalam" (PDF). filmsdivision.org. 15 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Mega Icons Season 1 Episode 1". Disney+ Hotstar. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Meet the man who's Kalam but not Kalam". India Today. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "'Rocket Boys' Begins Well, Then Turns Into Hagiography With a Blatantly Communal Touch". The Wire. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Chellappan, Kumar (8 December 2013). "True lies". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

External links

- Official website Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Website of Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam during his tenureship as the President of India, hosted by the National Informatics Centre

- A. P. J. Abdul Kalam at IMDb

- A. P. J. Abdul Kalam

- 1931 births

- 2015 deaths

- Defence Research and Development Organisation

- Indian aerospace engineers

- Indian Space Research Organisation people

- 21st-century Indian Muslims

- Madras Institute of Technology alumni

- People from Ramanathapuram district

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in civil service

- Presidents of India

- Engineers from Tamil Nadu

- Tamil engineers

- Tamil Muslims

- Tamil poets

- University of Madras alumni

- St Joseph's College, Tiruchirappalli alumni

- Nuclear power in India

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in science & engineering

- Fellows of the National Academy of Medical Sciences

- 20th-century Indian engineers

- 20th-century Indian politicians

- 21st-century Indian engineers

- Indian Tamil academics

- Indian Tamil politicians

- 21st-century Indian politicians

- People associated with Shillong

- People associated with solar power

- Academic staff of the International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad