Dmitrii Bogrov

Dmitrii Bogrov | |

|---|---|

דמיטרי בוגרוב | |

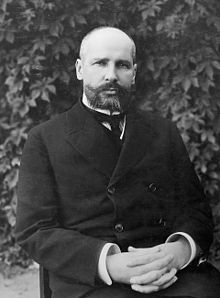

Bogrov in 1910 | |

| Born | 10 February 1887 |

| Died | 25 September 1911 (aged 24) Kyiv, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Assassination of Pyotr Stolypin |

| Political party | Socialist Revolutionary Party |

| Movement | Revolutionary socialism, Marxism, communism, anarchism |

| Criminal charges | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Capital punishment |

Dmitrii Grigor'evich Bogrov (Russian: Дмитрий Григорьевич Богров; 10 February [O.S. 29 January] 1887 – 25 September [O.S. 12 September] 1911) was a Ukrainian Jewish lawyer, known for his assassination of the Russian prime minister Pyotr Stolypin.

Raised in a wealthy Jewish family in Kyiv, Bogrov developed sympathies for revolutionary socialism from an early age and became involved with the Ukrainian anarchist movement while studying law at university. Disillusioned by the local anarchist group's activism, he was hired as an informant by the Okhrana and kept tabs on the group's activities. After graduating, he moved to Saint Petersburg in order to practice law and seek safety from the rising environment of antisemitism in the Russian Empire.

Disturbed by the pogroms in the Russian Empire and feeling guilty for his collaboration with the police, he began to plot the assassination of the Russian prime minister Pyotr Stolypin, who he held responsible for the attacks. He unsuccessfully attempted to elicit the support of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which caused him to have a nervous breakdown. After returning to Kyiv, he was confronted by members of his former anarchist group, who had discovered his involvement with the Okhrana and made threats against his life for it.

He again resolved to assassinate Stolypin. He told the Okhrana that assassins were planning to kill a government official, convincing them to grant him a ticket to the Kyiv Opera House, where the prime minister was due to attend a play. Having convinced the authorities that he was still on their side, he managed to get close to the prime minister and shot him twice. Stolypin died four days later. Bogrov himself was executed days after his target's death.

Bogrov's actions have become the subject of conspiracy theories, as well as numerous historiographical debates about his motives.

Biography

[edit]Early life and activism

[edit]Dmitrii Grigor'evich Bogrov was born in Kyiv, on 10 February [O.S. 29 January] 1887,[1] into a wealthy Jewish family.[2] His grandfather was a well-known writer and maskil;[3] and his father was a prominent lawyer in Kyiv, who had converted to Russian Orthodoxy.[4] Despite his father's conversion, Dmitrii himself continued to practice Judaism, which was the religion that was marked on his school diploma.[5]

The Bogrov family was deeply involved in left-wing politics: Dmitrii's cousin was a member of the Bolsheviks,[6] while his father supported the left of the Constitutional Democratic Party.[7] By the time he was a teenager, Dmitrii Bogrov himself had developed sympathies for revolutionary socialism and became involved in revolutionary activities,[8] initially as a supporter of the Union of Socialists-Revolutionaries-Maximalists.[6] He came to identify himself as an "anarchist-individualist",[9] as he resented formal organisation, rejected conventional morality and believed revolutionaries ought to operate alone under their own direction, even once declaring "I am my own party".[7]

Law education and informant activities

[edit]In the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution, Bogrov enrolled in the law school of Kyiv University.[10] As the government began cracking down on the revolution, Bogrov's parents sent him abroad to study at the University of Munich. There he familiarised himself with the works of Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, before returning in 1906 to resume his studies in Kyiv.[11] By December 1906, he had joined an anarchist communist group in Kyiv, but soon became disillusioned with their activities.[12]

Although his father paid for his education and provided him with a generous allowance,[13] Bogrov started to experience financial difficulties due to his gambling habit.[14] In February 1907,[15] he took a job as an informant for the Okhrana.[16] Working under the pseudonym of "Alensky",[17] he supplied the police with information on the Kyiv anarchists' activities.[18] Many the group's members were imprisoned or deported to Siberia during this period,[19] including its leaders Herman Sandomirskyi and Naum Tysh,[20] although it's uncertain how many of these were due to Bogrov's reports.[17]

By 1908, some of the group's members began to suspect that Bogrov was an agent provocateur.[19] Naum Tysh and Peter Liatkovskyi accused him of betraying them to the police, but he was defended against the charges by Sandomirskyi.[20] He also managed to convince Ivan Knizhnik and Juda Grossman that he was innocent of the charges against him.[21] In July of that year, Bogrov supplied the Okhrana with information about the bomb-manufacturing activities of the Maximalists, although he would later claim that he deliberately kept the exact address from them in order to prevent a police raid from taking place.[22] In September, he informed the police of a Maximalist plot to break Naum Tysh out of prison, resulting in the arrest of all conspirators. Bogrov himself took the opportunity to go abroad, where he told the editor of an anarchist newspaper that either Tsar Nikolai II or prime minister Pyotr Stolypin ought to be assassinated. He returned to Kyiv in April 1909.[23]

After graduating from university in February 1910, he decided to move away from Kyiv in order to work as a lawyer's apprentice in Saint Petersburg,[24] believing the city was safer for Jewish people than either Kyiv or Moscow, due to the rising environment of antisemitism and pogroms in the Russian Empire.[5] By this time, he had ceased all contact with the Okhrana in Kyiv.[25] After a few months in Saint Petersburg, he again approached the Okhrana and was hired as an agent,[24] working under the pseudonym "Nadezhdin".[25] But this time, he provided the police with unvaluable and even fabricated information,[24] later claiming he did this "for revolutionary purposes, so that I could make close contacts in these institutions and learn how they work."[25]

Assassination plot and motivation

[edit]

In June 1910, Bogrov contacted Egor Lazarev, informing him of his intention to assassinate the prime minister Pyotr Stolypin.[26] He claimed that his motivations were both personal and ideological, although he concealed his feelings of guilt over his past role as an informant.[27] According to Lazarev, Bogrov claimed that he sought revenge for the antisemitic pogroms that had been carried out in the Russian Empire and held Stolypin to be responsible.[28] He requested the official sanction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party,[29] declaring that he wished "to have the certainty that, after my death, there will remain people and a party who will interpret my conduct correctly, explaining it on the basis of a social and not from a personal motive."[30] Although Lazarev himself was worried about Bogrov's apparent indifference towards his own life,[31] he took the proposal to the party. The SRs were initially divided over their enthusiasm for the plan, but ultimately deciding against it, fearing that it would bring repression against the party.[32] Bogrov was devastated by the party's rejection and subsequently suffered from a nervous breakdown. On the advice of his physician and his parents,[33] he went abroad to Nice, in southern France, where he spent the next few months in recovery.[34]

By March 1911, Bogrov had recovered and returned to Kyiv,[35] where he attempted to resume his legal apprenticeship.[36] As rumours of his past involvement with the police circulated, he received an angry letter from Juda Grossman, who demanded answers, but Bogrov responded that he was no longer involved in political activity and refused to engage further in correspondence.[36] On 16 August, Bogrov was visited by a member of the anarchist group,[37] who informed him that the revolutionaries intended to kill him for his collaboration with the police.[38] When Bogrov asked how he could prevent this and "rehabilitate" himself,[39] they demanded that he assassinate a Tsarist official.[38]

Bogrov again committed himself to his plan to assassinate Stolypin,[40] who he considered to be the "source of all evil in Russia".[41] In late August, he went to the Okhrana and told them that revolutionaries by the names of "Nikolai Iakovlevich" and "Nina Aleksandrovna" intended to assassinate a member of the government during the Tsar's upcoming visit to the city, claiming they had a bomb and were staying at his flat.[42] Convinced of his reliability due to his past work as an informant, the Okhrana gave him a pass to attend the events, so that he could identify and apprehend the assassin. He was provided with a ticket to a performance of The Tale of Tsar Saltan at the Kyiv Opera House, where Stolypin was due to attend and where Bogrov claimed the assassin planned to carry out his attack.[43]

Assassination of Stolypin

[edit]

On the evening of 1 September, while police agents staked out Bogrov's flat, he went to the theatre and was questioned on the whereabouts of the assassins. He pretended to return to his flat and claimed that the assassin was still eating supper. Bogrov went to his seat in the seventeenth row, while Stolypin arrived and took his seat in the front row. Also among the attendees were Tsar Nikolai II, his daughters Olga and Tatiana, and the Bulgarian crown prince Boris.[44]

The performance started at 21:00. During the first intermission, Bogrov stayed back, as Stolypin was surrounded by other people. During the second intermission, at 23:30, Bogrov was ordered to return to his flat and keep tabs on the assassins. Noticing that Stolypin was standing alone, he decided that was the moment to act.[45] He made his way down the aisle towards the front row and all the way up to the prime minister.[46] When he arrived in front of Stolypin, Bogrov drew his revolver and shot him twice.[47] One bullet ricocheted off Stolypin's wrist into the orchestra pit and hit a violinist's leg, the other hit Stolypin in his chest, piercing through a medallion of Vladimir the Great.[45]

As those around the prime minister were left stunned by the attack, Bogrov calmly walked away towards the exit, making it halfway down the aisle before he was apprehended. He was disarmed and removed from the theatre by the police, while people attempted to aid the dying prime minister.[48] Stolypin was taken away to a clinic, but died four days later.[49] When the police raided Bogrov's flat, they found nobody there.[48] Russian nationalists in Kyiv responded by calling for a pogrom, but the authorities refused to support their invocation, as the Tsar was still in the city.[50] In order to pre-empt such a pogrom from taking place, Kyiv's Jewish community denounced Bogrov's actions and held a special service wishing health for the Tsar's family and to Stolypin.[51] For its part, the Socialist Revolutionary Party publicly denied taking part in the assassination.[52]

Interrogation, trial and execution

[edit]When he was interrogated about the attack, Bogrov confessed that he had fabricated the story of the two assassins so that he could get access to Stolypin.[53] He claimed that he had been threatened by revolutionaries due to their discovery of his past as an agent provocateur; he thought that this revelation alone was "worse than death" and desired to free himself from the guilt he felt due to his collaboration with the police.[54] He also repeatedly identified himself as a member of the Jewish faith and claimed that he was acting in the interests of the Jewish people.[55] He declared that he had not attempted an attack against the Tsar, as he feared it would have provoked further antisemitic pogroms.[56]

On 22 September [O.S. 9 September] 1911, Bogrov was tried by a court martial, which found him guilty of murder and sentenced him to death by hanging.[57] He was executed on 25 September [O.S. 12 September] 1911,[58] in Lysa Hora.[54] He died in the presence of thirty witnesses, including representatives of reactionary groups such as the Black Hundreds.[59] The religious representative at Bogrov's execution was Iakov Aleshkovskii, the Chief Rabbi of Kyiv.[5] In his final words to Aleskhovskii, Bogrov asked him: "Please tell the Jews that I did not want to harm them in any way, on the contrary, I struggle for their good and for the happiness of the Jewish people."[60] His death was mourned by young Jewish and Ukrainian radicals, who had sympathised with his motive's for assassinating Stolypin.[61]

Legacy and historical debate

[edit]Bogrov's assassination of Stolypin was the last major attack in a sustained period of terrorism in the Russian Empire,[62] which had started in 1866 with Dmitrii Karakazov's attempted assassination of Alexander II.[63] The assassination of Stolypin further destabilised the Empire, leading to its ultimate collapse in the 1917 Revolution.[64] Bogrov's actions have been compared to those of Marinus van der Lubbe and Lee Harvey Oswald, who likewise acted individually, but whose acts were nevertheless subject to widespread conspiracy theories.[65]

Since the assassination, there has been some historical debate about Bogrov's motives for the assassination and whether or not he acted on behalf of one group or another.[66] Although Bogrov acted alone, he was variously accused of acting on behalf of revolutionaries, reactionaries or even the police.[67] In his book A People's Tragedy, British historian Orlando Figes commented that this variety of possible explanations for Bogrov's actions stemmed from Stolypin having had enemies on all sides of the political spectrum: "Long before Bogrov's bullet killed him, he [Stolypin] was politically dead."[68] Documents regarding the assassination were also published in a heavily redacted form in 1914;[69] it took until 2003 for a complete volume of more than 700 pages of evidence to finally be published by ROSSPEN.[70]

The most common explanation for the assassination is that Bogrov was motivated by the threats against his life by the revolutionary anarchist group, a version which is supported by historians Abraham Ascher,[71] Anna Geifman,[72] George Tokmakoff,[36] and Jonathan Daly.[73] Geifman further suggested that Bogrov, known to have suffered from depression, had decided to commit suicide by way of homicide.[74] Russian historian Sergei Stepanov and American historian Victoria Khiterer have also theorised that Bogrov sought revenge for the recent pogroms in the Russian Empire.[75] American historian Norman Naimark depicted the actions of Bogrov and other Jewish assassins of the period as having resulted from the direct antisemitic oppression that they faced and a consequential disillusionment with the results of assimilation.[76] American historian Paul Avrich also considered the assassination to have been a "personal act" by Bogrov, rather than having been influenced by his associations with the police or revolutionary groups.[77] In his historical fiction novel The Red Wheel, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn suggested that Bogrov was motivated by protecting the interests of his Jewish family against rising Russian nationalism.[78] The 2012 Russian docu-drama Stolypin: A Shot at Russia likewise highlighted Bogrov's Jewish background as a motivation for the assassination, while also portraying his character as a gambler and insect collector.[79] This "Jewish motivation" has been disputed by Ascher and Geifman,[75] as well as Simon Dixon,[80] who each highlighted the assimilation of Bogrov's family into the Russian elite.[81]

Other hypotheses included that of Stolypin's own brother Aleksandr, who speculated that Grigori Rasputin had directed the assassination, although there is no evidence that Rasputin and Bogrov were ever in contact.[82] The hypothesis of police manipulation claims that the Tsar had become jealous of Stolypin's popularity and pressed the Okhrana to have him eliminated; but the Tsar himself had the power to dismiss ministers, so he could have already done so.[83] Solzhenitsyn also alleged Bogrov to have been working as a double agent for the Okhrana.[84] Yakov Protazanov's 1928 film The White Eagle also makes allusions to the culpability of the Tsarist government in Bogrov's assassination of Stolypin.[85] But allegations of a conspiracy on the part of the police are disputed, with evidence pointing to police incompetence rather than malice.[86]

References

[edit]- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 430; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 37; Geifman 1995, p. 238; Khiterer 2016, p. 430; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 173.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 430.

- ^ Daly 2004, p. 125; Khiterer 2016, p. 430; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Khiterer 2016, pp. 429–430.

- ^ a b Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 173.

- ^ a b Geifman 1995, p. 238.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 238; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 173; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 238; Khiterer 2016, p. 432.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 430; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, pp. 173–174; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 315.

- ^ Ruud & Stepanov 1999, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 238; Khiterer 2016, p. 432; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 174; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 174.

- ^ Figes 1997, p. 230; Geifman 1995, p. 238; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 174; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Ruud & Stepanov 1999, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 55n61; Daly 2004, p. 124; Dixon 2017, p. 29; Figes 1997, p. 230; Geifman 1995, p. 238; Khiterer 2016, p. 432; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 174; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 315.

- ^ a b Khiterer 2016, p. 432; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 55n61; Daly 2004, p. 124; Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 175; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 315.

- ^ a b Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 175; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 315.

- ^ a b Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 175.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 315.

- ^ Ruud & Stepanov 1999, p. 176.

- ^ Ruud & Stepanov 1999, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b c Khiterer 2016, p. 430; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b c Khiterer 2016, p. 432.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 352n107; Khiterer 2016, pp. 428, 430–431; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 316.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 316.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 431.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 352n107; Khiterer 2016, pp. 430–431; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 316.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 353n107; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 316.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 353n107; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 317.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, pp. 432–433; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 317.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, pp. 432–433; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b c Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Geifman 1995, pp. 238–239; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b Daly 2004, p. 125; Dixon 2017, p. 29; Geifman 1995, pp. 238–239; Khiterer 2016, p. 428; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 428; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 318.

- ^ Geifman 1995, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 433; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Daly 2004, pp. 124–125; Dixon 2017, pp. 36–37; Geifman 1995, p. 239; Khiterer 2016, p. 433; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 319.

- ^ a b Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 36; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 36; Geifman 1995, p. 239; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 319–320.

- ^ a b Tokmakoff 1965, p. 320.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 36; Geifman 1995, p. 239; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 320.

- ^ Daly 2004, p. 125; Khiterer 2016, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 353n110; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 321.

- ^ Daly 2004, p. 125; Khiterer 2016, p. 433.

- ^ a b Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, pp. 429–430, 434.

- ^ Geifman 1995, pp. 238–239; Khiterer 2016, pp. 433–434.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 239; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 239; Khiterer 2016, p. 434.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 434; Tokmakoff 1965, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 434.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 435.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 237; Naimark 1990, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Naimark 1990, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 436.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 321.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 29; Khiterer 2016, p. 428.

- ^ Dixon 2017, pp. 29, 37; Figes 1997, p. 230; Tokmakoff 1965, p. 314.

- ^ Figes 1997, p. 230.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Dixon 2017, pp. 36, 302n10.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, p. 428.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 240; Khiterer 2016, p. 428.

- ^ Daly 2004, p. 125.

- ^ Geifman 1995, p. 240.

- ^ a b Khiterer 2016, p. 429.

- ^ Naimark 1990, p. 184.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 55n61.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Wijermars 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Dixon 2017, p. 37; Khiterer 2016, p. 429.

- ^ Tokmakoff 1965, p. 314.

- ^ Khiterer 2016, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Naimark 1990, p. 172.

- ^ White 2016, p. 213.

- ^ Daly 2004, pp. 125–127; Dixon 2017, p. 37.

Bibliography

[edit]- Avrich, Paul (1971) [1967]. "The Terrorists". The Russian Anarchists. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 35–71. ISBN 0-691-00766-7. OCLC 1154930946.

- Daly, Jonathan (2004). "The Apogee of the Watchful State". The Watchful State: Security Police and Opposition in Russia, 1906–1917. Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 110–135. ISBN 978-0-87580-331-9.

- Dixon, Simon (2017). "The Assassination of Stolypin". In Brenton, Tony (ed.). Was Revolution Inevitable? Turning Points of the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–47. ISBN 978-0-19-065891-5.

- Figes, Orlando (1997) [1996]. "Last Hopes". A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924. London: Random House. pp. 213–252. ISBN 071267327X. OCLC 1277401748.

- Geifman, Anna (1995). "The End of Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia". Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917. Princeton University Press. pp. 223–248. ISBN 978-0-691-02549-0.

- Khiterer, Victoria (2016). "Appendix. Dmitrii Bogrov and the Assassination of Stolypin". Jewish City or Inferno of Russian Israel?. Academic Studies Press. pp. 428–436. doi:10.1515/9781618114778-018. ISBN 978-1-61811-477-8. S2CID 243243667.

- Naimark, Norman M. (1990). "Terrorism and the fall of Imperial Russia". Terrorism and Political Violence. 2 (2): 171–192. doi:10.1080/09546559008427060. ISSN 0954-6553.

- Ruud, Charles A.; Stepanov, Sergei A. (1999). "The Assassination of Stolypin". Fontanka, 16: The Tsars' Secret Police. McGill–Queen's University Press. pp. 173–200. ISBN 0-7735-1787-1. OCLC 45172454.

- Tokmakoff, George (1965). "Stolypin's Assassin". Slavic Review. 24 (2): 314–321. doi:10.2307/2492333. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2492333.

- White, Frederick H. (2016). "Interpreting History: Meaning Production for the Russian Revolution". Adaptation. 9 (2): 205–220. doi:10.1093/adaptation/apw003.

- Wijermars, Mariëlle (2016). "Memory Politics Beyond the Political Domain". Problems of Post-Communism. 63 (2): 84–93. doi:10.1080/10758216.2015.1094719. ISSN 1075-8216.

Further reading

[edit]- Geifman, Anna (2020). "Death-seeking turns political: A historical template for terrorism". In Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). The Routledge History of Death since 1800. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429028274. ISBN 9780429028274.

- Geifman, Anna (2022). "Terrorism as Veiled Suicide: A Comparative Analysis". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 45 (7): 608–625. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2019.1680185.

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2009). "The International Campaign Against Anarchist Terrorism, 1880–1930s". Terrorism and Political Violence. 21 (1): 89–109. doi:10.1080/09546550802544862. ISSN 0954-6553. S2CID 143397666.

- Khiterer, Victoria (2006). "Jewish Life in Kyiv at the Turn of the Twentieth Century". Ukraina Moderna. 10: 74–94. doi:10.3138/ukrainamoderna.10.074 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2078-659X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Lyubchenko, Volodymyr (2008). ""I Was Fighting for the Happiness and Welfare of the Jewish People", or Did the Assassin of Stolypin Have a Jewish Motivation?". Проблемы еврейской истории: 302–311.

- Miller, Martin A. (2015). "Entangled Terrorisms in late imperial Russia". In Law, Randall D. (ed.). The Routledge History of Terrorism. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315719061. ISBN 9781315719061.

- Rubin, Barry; Rubin, Judith Colp (2008). Chronologies of Modern Terrorism. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315705705. ISBN 9781315705705.

- 1887 births

- 1911 deaths

- Anarchist assassins

- Assassins of heads of government

- Executed assassins

- Executed anarchists

- Executed revolutionaries

- Executed Ukrainian people

- Individualist anarchists

- Jewish anarchists

- Okhrana informants

- People convicted of murder by Russia

- People convicted of murder by military courts

- People executed by armed forces

- People executed by the Russian Empire by hanging

- People from Kiev Governorate

- People from Kyiv

- Socialist Revolutionary Party politicians

- Secular Jews

- Ukrainian anarchists

- Ukrainian assassins

- Ukrainian people convicted of murder

- Ukrainian Jews

- Ukrainian revolutionaries

- Ukrainian socialists

- Civilians who were court-martialed

- Inmates of Kosoi Kaponir Fortress